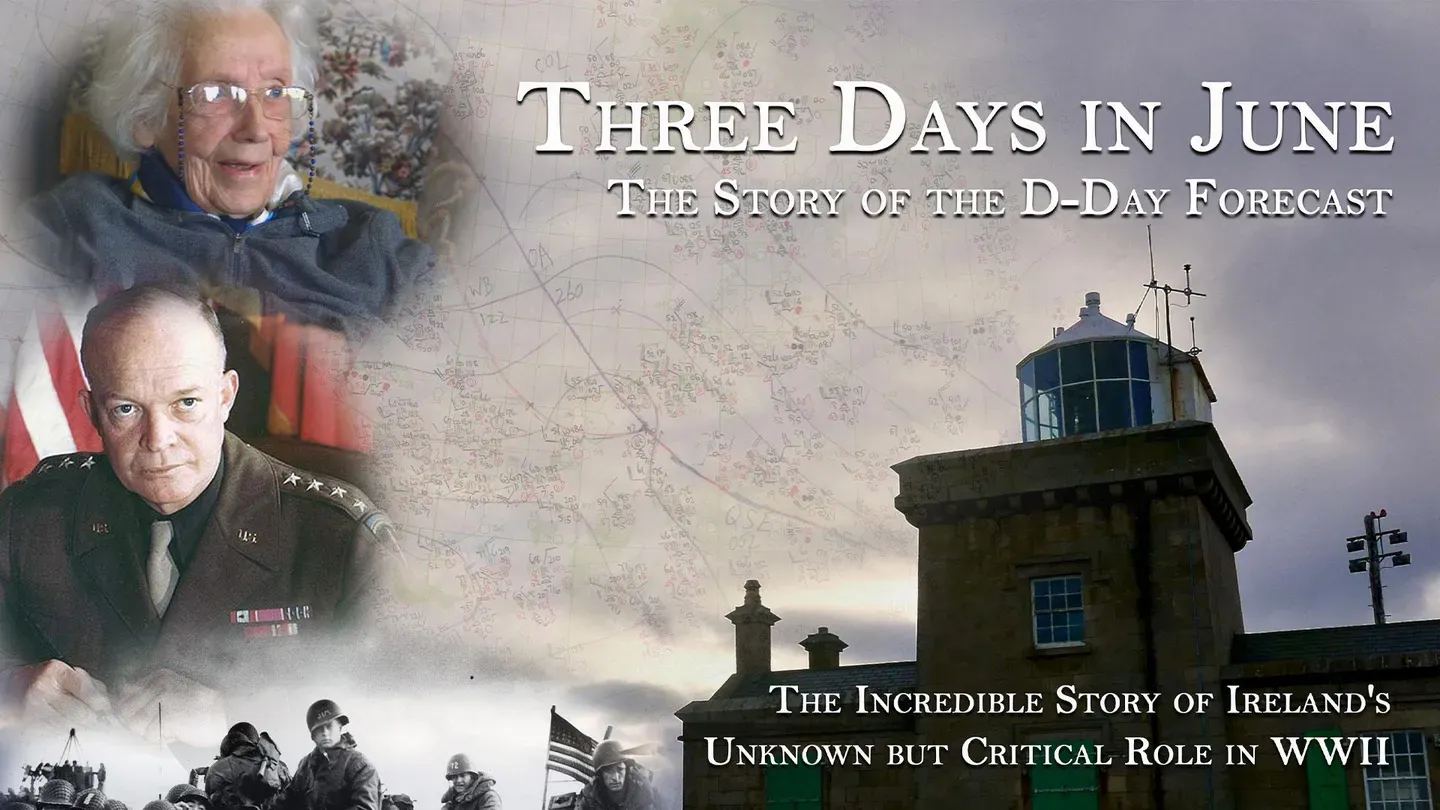

The Story of the D-Day Forecast: Three Days in June

Special | 52m 34sVideo has Closed Captions

Discover Ireland’s previously unknown role in the pivotal D-Day military invasion.

In June 1944, the success of the D-Day military invasion was completely reliant on weather readings taken by a young woman, Maureen Sweeney. Including a special interview with Sweeney and contributions from Susan Eisenhower (granddaughter of the General), historian Antony Beevor, and others, follow this unique moment in history where military might and meteorological analysis collided.

The Story of the D-Day Forecast: Three Days in June is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

The Story of the D-Day Forecast: Three Days in June

Special | 52m 34sVideo has Closed Captions

In June 1944, the success of the D-Day military invasion was completely reliant on weather readings taken by a young woman, Maureen Sweeney. Including a special interview with Sweeney and contributions from Susan Eisenhower (granddaughter of the General), historian Antony Beevor, and others, follow this unique moment in history where military might and meteorological analysis collided.

How to Watch The Story of the D-Day Forecast: Three Days in June

The Story of the D-Day Forecast: Three Days in June is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

(somber music) (man) West, nine knots, fair, seven miles, 1,026, rising slowly.

(inaudible) southwest, 60 knots, mist, four miles, 1,021 rising... ♪ (Joe) I think we owe a lot to Maureen of the west of Ireland, us who invaded France on D-Day, because if it hadn't been for her reading of the weather, we would've perished in the storms.

♪ (Maureen) I feel very happy about it that we did give the right readings.

Oh God I feel proud.

♪ (inaudible) from Blacksod.

♪ (General Dwight Eisenhower) Your task will not be an easy one.

Your enemy is well-trained, well-equipped, and battle-hardened.

He will fight savagely.

(Susan) There was so much at stake.

So much at stake.

I think Nazi Germany could not imagine in their wildest dreams that we would be crazy enough to make that assault on that day.

♪ (dramatic music) ♪ (man) Without even bothering to declare war, the German armies launched a coordinated attack across the neutral borders of Luxembourg, Belgium, and Holland, from the Maginot Line north to the sea.

(Antony) On the 10th of May, 1940, Nazi Germany attacked Luxembourg, Holland, Belgium, and France all on the same day, the very day that Churchill became prime minister.

At this stage of the war, Britain had a small army still which was on the continent, the British Expeditionary Force.

In late May 1940, the French were broken, and the British found themselves having to retreat towards Dunkirk.

(President Franklin Roosevelt) The hand that held the dagger has struck it into the back of its neighbor.

(Robert) The imminent defeat of France triggers a widespread belief across Europe that the future belongs to Hitler and the Nazis.

So, if you look at the map of Europe, it looks as if the democratic regimes of the West are finished and as if the future of Europe is actually totalitarian, either fascist or Bolshevik.

So, it looked as if democracy was definitely on its way out.

(man) One of the greatest disasters in history seemed in the making.

An entire British army faced annihilation.

But out of the fog and the mist, shrouding the Channel came a strange armada of navy craft, fishing boats, pleasure yachts, anything that would float.

The seagoing people of Britain had come to rescue their army.

(dark music) (Antony) Dunkirk was the one moment when Hitler could've won the whole of the Second World War.

(plane droning, exploding) ♪ The weather was, of course, one of the key elements of all.

It was calm.

There was very few waves so ferrying the troops out to the warships was possible.

They hoped, as a maximum, to take out 45,000 troops.

In the end, they took out something like 338,000.

The survival of the British army meant that there were troops ready for the day when they would be able to cross the Channel again and liberate Europe.

♪ (announcer) In December 1943, at Tehran, Persia, the date for the liberation of the people of Europe was set on the Allied calendar of operations.

Destroy Hitler's empire.

Smash it by air, break it wide open, then invade by sea.

That was the directive.

(Susan) The war had been building to a crescendo, and the Soviet Union was really pressuring the Allies to open a second front because of the tremendous casualties they'd taken on the Eastern Front.

And at the Tehran Conference, Joseph Stalin was not having any of this someday soon.

He said at the conference on two or three occasions, "What is his name?

What is the commander's name?"

And he demanded to have a name.

And, so, when that conference was over, the United States and Great Britain understood that they had to have a name.

(Major Joseph Skelly) December 7th, 1943, two years after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt sent a terse message to Marshal Stalin that General Eisenhower had been appointed to lead the invasion of Normandy.

He had shown in the North African campaign that he could organize disparate troops from the United States and Great Britain into a cohesive fighting force.

(Susan) So imagine Dwight Eisenhower, who at the time of Pearl Harbor was a one-star general, is given the most prized command of Allied Forces which was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force.

(Lt. Gen. Richard Trefry) He was a very brilliant man.

He loved the military in a good way.

He wasn't a tyrant, but he had tremendously high standards.

If you were gonna work for him, you were gonna be a perfectionist.

He's the guy I think that gets attributed to the statement: "A plan is useless.

Planning is everything."

And if you stop and think about that, that's the kind of a guy you want running something like D-Day.

Teamwork wins wars.

I mean teamwork among nations, services, and men.

(ominous music) All the way down the line from the GI and the Tommy to us brass hats.

(waves whooshing) (soft music) ♪ (Maureen) I meant to go to America, but I didn't get that far.

♪ I answered an ad for a post office assistant.

There wasn't a mention about weather.

And I arrived up, and it took me two full days and part of the third day to get here.

(bicycle clicking) I always loved the sea and the strands, and when I saw that, I said, "I'm going to give this a try anyway."

♪ (Gerald) Maureen Flavin, as she was then, replied to an advertisement for a postmistress's assistant, and only when she got there did she realize that, in fact, the postmistress had as a sideline, to an extent, a contract with the Irish Met Service to provide weather observations and that part of her duties would be to do these weather observations.

(clock ticking) (Maureen) Well, there was no learning unless you fell into it automatically.

I didn't like night duty.

I used to be afraid of the Germans to come in at night... (chuckling) ...come ashore!

♪ (man) Éamon de Valera, pursuing his dream of a self-sufficient and peaceful era, has succeeded in maintaining his nation's complete independence on the issue of neutrality.

Ninety-five percent of Erin's people were convinced that to enter the war on Britain's side would have been to betray the cause of independence to which Ireland's heroes devoted their lives, men like Daniel O'Connell who won for Ireland's religious emancipation... (dark music) (David) The outbreak of war presented de Valera with a balancing act.

He wanted to stay neutral.

He felt it was absolutely vital to assert Irish sovereignty through remaining neutral.

He also thought it was vital to protect the Irish people because they had absolutely no defense against an air attack.

So he was really relying on the power of the Royal Navy and the RAF to save him and to save Ireland.

♪ (Robert) The Germans believe that Ireland might actually provide some kind of route to attack Northern Ireland in particular, that they could rely on the support of Irish Republicans who would team up with whoever was an enemy of Britain in order to achieve a united Ireland.

♪ (David) Hitler was well aware that if the Luftwaffe had access to bases in Ireland, they could close the ports that were keeping Britain in the war.

And he said at one point that possession of Ireland could lead to the end of the war.

♪ (Robert) There are various plans being devised.

One plan is to actually land troops in the south of Ireland with senior figures in the IRA to actually land German troops in Northern Ireland where they would occupy Northern Ireland and, then, at least, that's the hope of some IRA figures.

The Germans would then allow a sovereign All Ireland at the mercy of the German state.

♪ (Major Joseph Skelly) Éamon de Valera had to walk a fine line at home and abroad as he maintained Ireland's neutrality.

At home, in his rear guard, he was facing an Irish Republican movement that was sympathetic to the Nazis.

In the United Kingdom, he was facing great pressure from Winston Churchill to join the war effort on the side of the Allies.

Yet, the Irish people supported the policy of neutrality.

And Éamon de Valera was able to thread that needle and maintain neutrality during the war.

But again, it was a neutrality that, overall, sympathized with the Allies both in word and in deed.

(David) It's estimated around a hundred thousand Irish people went to work in British war industries.

Around about 70,000 people joined the British Armed Forces.

So, those are big numbers.

De Valera in public maintained a strict neutrality, but in private, he was prepared to do what he could to help the British as long as it didn't become public.

(engines puttering) And in complete defiance of the ordinary rules of neutrality, he agreed that they could fly over Donegal, over what was called the Ballyshannon Corridor.

There was intelligence cooperation.

There was cooperation on planning for British reinforcements if the Germans should invade.

The main thing was the weather.

They were absolutely obsessed with getting information about the weather from Ireland.

♪ (Catherine) The reason we were receiving data from Ireland was because of an agreement which was reached in September 1939, when it was decided that data from six locations in the Republic of Ireland would be shared with the UK.

And you can see these on the chart.

And they would be critical data, particularly located on the very west, so that's Blacksod Point and Valentia, because they were the locations where the weather would first hit land.

(Gerald) The agreement that the Irish observations were made available to Britain wasn't just that they were put out there for everybody to use.

In fact, they were coded, and those codes were actually supplied by the U.S.

So this is an indication of the very, very close working relationship there was on the ground between the Irish Met Service, as it was then, and the Allied war effort.

(fanfare music) ♪ (General Dwight Eisenhower) I assumed command at Shaef with the best all-around team for which a man could ask.

Some had already been working for months in England.

Others, I brought with me from the Mediterranean.

We adopted first a master plan and, then, had to coordinate every last detail of the ground, sea, and airplanes.

(Colonel Jeremy Green) Eisenhower, a brilliant staff officer, a consummate diplomat.

He describes his role as Supreme Commander as being like chairman of the board seeking a consensus.

And Eisenhower's great gift was being able to hold this pretty fractious coalition together as the American star was in its ascendency, and the British Empire's was in decline.

And he was alleged to have said: "I don't mind if you don't get on.

I don't mind if you fall out.

You can call each other 'bastards,' but I'll sack anyone if you call 'em a 'Yank bastard' or a 'Limey bastard.'"

(Susan) Oh, I have many memories of my grandfather.

I was about 17 years old when he died.

And we lived on a property adjacent to the Eisenhower farm, so I saw him nearly every day.

He had this enormous capacity to rationalize what looked like different viewpoints and to find common ground.

I watched some of that even as a kid.

And he had a consolatory nature even though he could be very tough-minded.

I think some of that came from the fact that, get this, he was one of seven boys and he was the middle child.

He had a very aggressive, outspoken older brother.

He had two other younger brothers who needed protection, and he was the kid who was always putting it together.

(plane droning) (melancholy music) (Major Joseph Skelly) The maxim of military planning is that the weather is neutral.

General Eisenhower knew different.

He knew that the weather could be a friend or a foe.

He understood his history.

He knew about how the Spanish Armada was dashed upon the rocks of Scotland and Ireland.

Theobald Wolfe Tone saw how stormy weather on the west coast dashed his hopes of a French invasion.

So, in the planning for Operation Overlord, the weather was an integral part of the process.

And this was true even if those reports came from a small outpost at Blacksod on the Mayo coast.

(waves whooshing) (somber music) (Maureen) It was only every six hours pre-war, but I found out that our weather reports were the first indication of either good or bad weather coming in.

And I made it an hourly one.

We'd only have one finish, it would be time to take another.

The reports from here show the first changes coming off.

(melancholy music) (Dr. Rodney Teck) Maureen would've recorded the temperature.

She would also have recorded the water vapor and the pressure.

That information was transmitted from Blacksod through the telephone exchange in Ballina.

From Ballina, then it would have gone to Dublin, and Dublin then would have transmitted that information by teleprinter directly to Dunsmore in the UK.

♪ (Colonel Jeremy Green) The weather in Ireland was critical.

There was no doubt about that.

There was a huge gap in capability in forecasting to the west of the British Isles.

We couldn't see that far, but the weather stations in Ireland could.

(violin music) (Catherine) James Stagg was a very important man in the critical D-Day forecasts.

He was a dour Scot.

He was 6'2.

He was commanding.

He was a very strong character and very skilled meteorologist.

But his task in this case wasn't actually to do all the forecasting himself.

It was to pull together various different strands coming from the American forecasters and from the British forecasters, all of whom had teams looking at the same data and coming up with their own forecasts and on the whole, not agreeing with each other.

The American team, led by Irving Krick, used a method of forecasting called "pattern recognition," so they were essentially looking at the data and saying, "Well, in the past, this is what usually happens."

That was effective to a certain point, but it wasn't the way that modern forecasting was really going.

However, they were absolutely certain that they could absolutely predict what would happen.

(Professor John Sweeney) The British, on the other hand, were constructing charts which showed them where the low-pressure centers or the high-pressure centers were and then how fast they were moving by comparison to the previous chart, maybe an hour or two earlier or a day or two earlier.

A much more sophisticated consideration of what the physics of the atmosphere were doing rather than the history of the atmosphere.

(Susan) Stagg really brought a very special perspective to weather forecasting.

He was an atmospheric scientist who was intrigued by the connection between what was going on in the upper atmosphere in weather and what was going on on the ground.

But, you know, it was a big gamble for the Supreme Commander at the start, and he had to have confidence in the people who were giving him advice.

♪ (James Stagg) General Eisenhower could tell even before I presented the forecast each time what I was going to say.

He used my face, I think, as a kind of hall barometer.

(dark music) (Susan) As D-Day got closer and closer, Dwight Eisenhower kept track of the weather forecast he was being given and, then, would compare them with the way the weather actually turned out.

(Professor John Sweeney) He had been tracking what Stagg had been saying would happen, and I think he was quite impressed by Stagg's credibility in terms of forecasts.

Stagg's great attribute was his honesty.

He was very blunt.

And he gave advice which was very impartial and very reliable, and so he was trusted by Eisenhower.

(man) I'm confident, sir.

(Colonel Jeremy Green) Meteorology at this stage of our history was more an art than a science.

For Dunkirk, certainly, it was key.

And it's interesting that then replays for the D-Day story where weather is the sole determining factor for Eisenhower's decision to go or to postpone the invasion.

♪ (man) Along the Channel, where the sea strikes France, stood the west wall of concrete, stone, and steel to mock the frail hopes of the petty free.

Wounded, hard-dressed, and wasted in our strength, almost like madmen then, we planned to breach the wall and smash the German smite.

But where?

(ominous music) (Robert) If you look at the map of Europe in 1940 and in the summer of 1944, occupied Europe looks pretty similar in a very superficial way.

But despite all of that, there are significant differences.

Germany had already lost roughly half of the total of six million German soldiers who would lose their lives over the course of the Second World War, which means, increasingly, you had either very young soldiers that had been drafted into the army or relatively old men who, under normal circumstances, would not have served in the German army.

♪ There's also the issue of morale, of course.

Most German families would have lost sons, husbands.

♪ There was a growing doubt that Germany would win the war.

♪ (Colonel Jeremy Green) The British, we were tired by this stage.

We'd been fighting the war since '39.

We'd been alone for a bit.

The country was completely mobilized.

We were one of the few of the Allies that mobilized the entire nation.

And Montgomery had been told the nation couldn't replace his battle casualties.

There was political decisions to be made about lowering the age of conscription to 16 which was unprecedented.

♪ (Susan) There was so much at stake.

Not only was the future of Western Europe at stake, but we had the Holocaust and the extermination of millions of people in the most horrific ways.

♪ The Germans were working as hard and as fast as they could to develop a nuclear weapon.

We had all kinds of advanced technology that was aimed on Great Britain, the V1 and V2 rockets.

(man) They come droning and sputtering and roaring, and you don't know when they'll suddenly stop and drop on you.

(exploding) (Susan) So everything depended on D-Day, and it turned out that one of the very key variables here, of course, was the weather.

(soft music) ♪ (Vincent) My mother, Maureen, had responsibility for recording weather data.

She did this using rudimentary instruments and equipment placed in the corner of the little post office in a remote spot, a world away from the bloodshed and tragedies of the war.

♪ (wind howling) (Maureen) Wind direction was very important.

You'd have to be precise with that.

Living here, we'd know the wind directions by heart.

But this day, it was kind of too bad to know the exact direction.

So, I said, "Ring the Coast Guard."

(chuckling) It was ringing a while before he answered me.

I swear he was probably asleep.

But I asked him anyway, I sent him the north way.

I can't get the wind direction.

How's it blowing?"

(unintelligible) (laughing) I clapped down the phone.

♪ (Vincent) People around here gathered in their homes.

They played cards, went to a few dances.

But they had no idea of the significance of the weather report from Blacksod and the part it was to play in the war.

(birds squawking) (man) Faint across the groaning of the sea came the thin thunder of a massive power.

Drawn from the great free peoples of the earth, it gathered in the ancient ports of England to crowd upon the steel-encumbered ships.

(dramatic music) ♪ (Colonel Jeremy Green) D-Day staggers me.

The size, its complexity, the technology of artificial ports constructed in the UK by 55,000 workmen with the internal capacity of a thousand football pitches, an overlay of a deception plan of double agents and radio traffic.

(man) This is London calling the European news service of the British Broadcasting Corporation.

Here are some messages for our friends in occupied countries.

The Trojan War will not be held.

John is growing a very long beard this week.

(Colonel Jeremy Green) Even to the extent of encouraging the French Resistance to knock out telephone lines in France so the Germans were forced to use their radios and their Enigma traffic which we could decode and crack.

(tense music) ♪ Eisenhower arrives here on the 2nd of June, and the routine in headquarters was there were two briefings, one in the morning, one in the evening on the weather.

And Stagg would go into the library with all the generals, admirals, and air marshals and talk to them about the weather.

(Catherine) James Stagg had a very challenging task ahead of him, some would say impossible.

He was requested to provide a five-day forecast.

Difficult enough in modern times.

Almost impossible with the amount of data available to him in 1944, but that was, nonetheless, his task.

(Gerald) We had a very narrow window of opportunity which was connected with the tidal conditions because these small boats are very susceptible to the sort of waves and swell coming onshore onto those beaches.

♪ (Professor John Sweeney) You didn't want them to be bobbing around close to the shore under fire and people trying to jump out of them.

And as well as that, of course, the troops had very heavy backpacks on, so when they jumped out of the landing craft, if there were strong waves, they would be upended very quickly.

(waves crashing) (Gerald) Wind, really as little as possible.

What they're looking for is the pressure to be rising because high pressure typically brings these settled weather conditions which might give them 12 or 24 hours of relatively settled weather to get their ships across the Channel and get their men onshore.

(Professor John Sweeney) You also had to have visibility for the bombers to make sure that they could see their targets.

So you had to have a full moon.

♪ Without all of that combination occurring, the next optimum time for landing would have been two or three weeks away from the 4th, 5th, 6th of June and the cat might have been out of the bag by then.

The Germans might have been prepared.

(waves whooshing) (man #1) It was vital to know all about the sand there and the tides.

(man #2) And retrain the men to negotiate those tides in landing craft.

(man #3) Wearing down German seapower in preparation for the day.

(man #4) Special study of the weather along the Normandy coast.

(man #5) Miles of wire netting for the beaches.

(man #6) 7,200 tons of petrol per day.

(man #7) With an underwater pipeline to carry it to France.

(man #8) A white star is the emblem of liberation.

(man #9) Triple inoculation for all personnel.

(man #10) New ships pouring from the stocks, old ships adapted.

Listening to the German radio output for fresh intelligence.

(man #11) That was just part of the pre-invasion work.

(ominous music) ♪ (Antony) The crossing of the Channel to Normandy was a vast enterprise.

♪ It was beyond anything which anybody had ever imagined.

I mean, the Canadians started to make jokes about Operation Overboard simply because the plans and instructions ran to hundreds of pages of orders in every single issue.

♪ (Richard) Everything before D-Day came from the west coast, as far as Scotland, as Northern Ireland and Wales.

Everybody would come anti-clockwise as they came along, all the while being reinforced from ports all along the coast.

They eventually met up at Piccadilly Circus, Point Zulu just off the Isle of Wight.

6,971 ships taking 130,000 soldiers across the Channel.

(woman) Of course, we only saw it happening on the wall map and, yet, it was, well, quite real.

When I started there, those markers we used reminded me of toys out of some children's game.

But soon, they became U-boats and ships carrying cargos, food, and supplies, and weapons, and men to use them.

(horn blaring) (somber music) ♪ (Joe) I wasn't due to go out to Normandy for nine days after D-Day, but my sergeant major came up to me.

He said, "And where do you think you're going?"

I said, "I'm going back to camp."

"Oh, no, you're not."

I said, "Yes, I am."

He said, "No, you're not!"

He said, "You're going to drive that vehicle over there."

He said, "The driver's been injured.

You've got to take his place."

And that's how I came to be on D-Day.

(soft music) And we realized that this wasn't an exercise anymore, because you could see thousands of men, vehicles, and ships all round you, and you realize that this must be the invasion fleet.

Then you begin to get worried and you think to yourself, "What have I let myself in for?"

(birds squawking) (waves crashing) (solemn music) (Vincent) On June the 3rd, my mother saw the menace coming in from the ocean before anyone.

The pressure dropped on the barometer.

The northwest winds picked up, rain and low clouds swept across the Mullet Peninsula.

♪ There are my figures.

♪ Yeah, there they are in notes.

The 3rd of June, that was my birthday.

(Gerald) We're here on the night of Friday the 2nd, Saturday the 3rd of June, 1944, and it's one o'clock in the morning and here's Maureen's initials.

Maureen Flavin as she was then.

She's out on her 21st birthday, one in the morning doing the weather observation.

And what does she spot here but the change in pressure, -21, -22, -20, -21.

The pressure falling away, that was the red flag.

(wind blowing) (Vincent) From Blacksod to the Normandy beaches is just over 500 miles approximately.

The storm that came in that my mother observed was traveling roughly at 35 miles per hour.

That would have reached the beaches of Normandy at 0500 on the 5th of June, D-Day.

(telephone clicking) (soft music) ♪ (telephone ringing) (man) Hello?

Hello, Maureen.

(John) When Maureen sent the observation on to the authorities in Dublin, she resumed her normal activities, but then received a phone call two hours later.

(telephone ringing) ♪ Hello, Blacksod.

(Maureen) It was only dawn when the phone rang to please check and repeat.

I said, "What's wrong?"

And of course, they weren't going to tell me they were going to war.

♪ (Gerald) The fact that Maureen would've got a call indicated that this reading was really important, because it was forcing the forecasters to actually change their view of what the weather was doing.

There was a big weather system out there, probably bigger than they had anticipated, than they had imagined.

♪ (Antony) Group Captain Stagg is extremely disturbed to hear that the Blacksod Weather Station on the West Coast of Ireland is reporting 4-6 gales.

♪ They're reporting a rapidly dropping barometer.

All of this is very alarming and very dangerous news indeed.

(Catherine) Here is Blacksod.

Showing you pressure dropping in every instance, which usually means bad weather.

And Stagg would have been looking at these and thinking, "What am I going to suggest we do?

We've got this front, we've got this front.

Low pressure's packing in one behind the other.

Where am I going to suggest that there's any sign of hope?"

♪ (pensive music) (Richard Trefry) Stagg looks at all this stuff, and suddenly he says, "You know, here's an arctic front.

And here's a Bermuda high.

We're gonna make beautiful music on this turkey."

♪ This warm front and the cold front are gonna cause us a hell of a lot of problems if we go on the 4th.

♪ (Susan) Group Captain Stagg had not only a lot of courage in finally making this fateful weather forecast, but a lot of courage in delivering it to the Supreme Commander, who certainly, on June 4th, didn't like the answer.

(Jeremy) Eisenhower had no choice.

Now, Eisenhower had basically said, "We need to rely on our air superiority.

If the air can't operate, we have to postpone."

He then did what Eisenhower always did, which looked around the room and said, "Are there any dissenting voices?"

And he asked each of the component commanders, Montgomery, Leigh-Mallory, and Ramsay whether they could.

Ramsay thought they could, but they wouldn't be able to do a follow-on force invasion.

Leigh-Mallory was deeply, deeply pessimistic.

Montgomery was concerned that some of the troops were going to lose their fighting edge, but Tedder sort of had the casting vote, and Tedder thought not, so Eisenhower postponed.

(solemn music) ♪ (wind blowing) (suspenseful music) ♪ (Joe) We were brought to a halt.

We expected to go back on land again, but they didn't, they kept us on board ship.

The poor lads, these infantry blokes, they were laying all over the deck being sick and unhappy and crying for-- some of them were crying for their mothers.

And we began to wonder what the generals and that were thinking about sending us out on a storm-ridden day like that.

(wind blowing) (man) We all knew that there could be only one day's deferment.

If there had to be another day, then all the landing craft would need to return to base for a whole fortnight until the next tides were right.

And our charts were so black in the Atlantic that there didn't seem to be any prospect of getting this operation going at all.

(soft music) ♪ (Antony) When soldiers really hyped themselves up to prepare themselves and then they're told to stand down, that actually has a very serious effect on morale generally.

♪ The pressure on Eisenhower was simply appalling in that particular time.

Any major postponement of Operation Overlord would have been disastrous.

(Susan) From all accounts, he had a kind of fatalistic view about this.

Certainly, Ike is well-known to have smoked a few packs of cigarettes.

That would be three or four.

Probably four during that period.

Lots of coffee, et cetera.

And, you know, I look back on that and I think there are few people who had to manage a moment like that in history, and he was one of them.

♪ (Maureen) Poor old Eisenhower.

He was Commander-in-Chief.

All the proposals had to go through him.

He had the whole world, I suppose, to consider.

(dramatic music) (Robert) At the same time in Berlin, you have senior politicians like Joseph Goebbels, the Propaganda Minister of the Third Reich, who suggests in public speeches that they would welcome an Allied invasion, because finally, they could meet them on the beaches.

♪ (Antony) There was tremendous bombast coming from the Nazi leadership.

Goebbels was basically saying, you know, "If they're not coming, why don't they come?"

And Hitler had convinced himself that this was the opportunity to destroy the Allies, to throw them back into the sea, and then he'd be able to concentrate all his forces on the Eastern Front against the Red Army.

♪ Rommel was Commander-in-Chief of all of Northern France, but he did not have control over the panzer divisions.

He was desperate to persuade Hitler to allow him to have a couple more panzer divisions to defend the beaches in Normandy, because by now, Rommel was pretty sure it was going to be Normandy.

(Robert) Hitler views himself as a military genius and he, in this case, is undecided.

There's no clear decision as to how to organize the defense of France, and the means which Rommel has at his disposal are very difficult to compare to the situation of the German Army in 1914.

(Antony) It was Rommel who came up with the phrase, "the longest day," because he said, "That first day will be the longest day in the sense that, if we don't win on that particular day, then the Allies will be ashore and we won't be able to defeat them."

(ominous music) ♪ (waves crashing) (tense music) (Gerald) On the 4th of June, Maureen was just going through the steps which she had been trained to do to read the barometer, read the thermometer, read this, read that, completely oblivious to the decisions that were going to be taken in the next while, which were at least partly dependent on what she was doing.

♪ (Maureen) You went out at 10 to the hour night and day Sunday and Monday.

You couldn't get a good night's sleep.

You do one weather report sent, it was time to go out and take another one.

(Gerald) Here now, we're at nine o'clock in the morning, and again, Maureen is back on duty, doing her observation, and the pressure is still falling, but going on through the morning, that fall eases off, -7 at midday, and by the time we get into the afternoon, it's changed, and we're beginning to see a rise in pressure.

The first signs of it apparent here in these observations from Blacksod.

♪ (Rodney) A high pressure system built a ridge of high pressure along the west coast and stopped dead in its tracks the next set of depressions, which were out in the Atlantic.

And it was this miracle, because I can only call it a miracle, that allowed Stagg to say to Eisenhower, "Look, Commander, I think you might just have 12 to 24 hours to actually go ahead on the 6th."

(waves crashing) (telegraph clacking) (soft music) (Catherine) 4:15 in the morning on the 5th of June is a critical time.

That's when Eisenhower and the Joint Chiefs met to be briefed by Stagg.

At the time they're making the decision, the weather's appalling in Portsmouth, in Southwick House.

Absolute confirmation that they were correct to cancel for the 5th, but at the same time, they had to really trust Stagg and his team that he could definitely see a weather window improving, because as far as they could see, if they were looking out the window, there'd have been absolutely no indication of that at all.

(Richard Trefry) Stagg told him, "If you want to go, the 6th is the date.

You go on the 7th, you're gonna get in trouble."

You've seen what the hell happens the last three or four days around here.

And you get these people all loaded up in shifts, they're all climbing in each other's skivvies, it's a mess.

You can't imprison guys on something like this.

(Jeremy) Stagg recognizes the readings are changing, the pressure's going up, a cloud is dropping that's gonna be an impact on the surface weather and particularly on the seas, and that's when he can say to Eisenhower with confidence, I think it was his confidence alone, based upon what he'd got from Ireland that he says there's going to be an interlude in the weather sufficient to get the troops ashore.

(Stagg) When I could tell them that the fine interlude would indeed come along, the joy on the faces of the Supreme Commander and his commanders after the deep gloom of the preceding days was a marvel to behold.

(Antony) In that moment, Ramsay had to say, "Within half an hour, I have to be able to give orders to the fleets, because otherwise it's going to be too late to turn them back."

This is the key moment when Eisenhower turns to Montgomery and says, "Do you see any reason why we should not go on Tuesday the 6th of June?"

And Montgomery says, "Nope.

I say go."

So it was a pretty dramatic moment.

♪ (Susan) Eisenhower realized that they had done everything they could, that they had run the traps on absolutely everything, and somebody had to make the decision.

Just think about it, the eerie feeling of all of this preparation, all of this preparation, and then you say, "Okay, let's go," and then it's out of your hands.

♪ (Jeremy) The irony was that having made the decision based upon the weather forecast that Stagg had given him, he was now powerless.

He was the Supreme Commander, but he couldn't change the plan, he couldn't modify it.

This immense machinery of war was moving towards the beaches of Normandy.

(wind blowing) (Joe) It was dark and stormy.

There was a bit of a gale blowing.

The sea was quite rough.

It was pelting down with rain, and it was really terrifying.

And we began to wonder, "Why are we going across on a day like this?"

(water splashing) (dramatic music) (narrator) Within steel and concrete emplacements four years in the making, the Germans have amassed every known weapon of defense.

Whether those weapons are enough to stop the Allied onslaught will be proven in the struggle that lies ahead.

♪ (tense music) (Antony) One of the great advantages for the Allies was that the Germans had no weather ships in the North Atlantic.

As a result, they had no idea of the break in the weather, which might be arriving.

(Catherine) The German forecasters were just as skilled as the British.

In fact, arguably, potentially more so, but as you can see from this German chart, they have absolutely no vision of the Atlantic, which is where all of this weather was coming from.

And so they couldn't see that pressure rise.

They couldn't see the Blacksod observations.

They did not see that very slight improvement, which allowed the weather window on the 6th.

(Robert) The weather information that the Germans had in the lead up to the D-Day landing basically suggested that a big storm was coming and that it would be impossible for any Allied armada to land anywhere in Northern France.

So lots of senior officers, including Rommel himself, took a few days off.

Rommel went to Germany for his wife's birthday, so in this context, of course, the much more accurate weather readings that the Allied had proved to be a huge advantage.

(Antony) Eisenhower did not know for certain, of course, whether this vast project was going to turn into one of the worst disasters of the whole war, and as a result, he wrote the statement preparing himself to announce, basically, the failure of the whole of Operation Overlord.

(Susan) Just after he'd made that consequential decision, my grandfather took out a small piece of paper and he wrote a communiqué to be issued in case of failure.

He said, "If there is any fault that attaches to this, it is mine alone."

And this accepting full responsibility, even when the critical factor is the weather itself, is seen still today as an extraordinary statement of accepting personal responsibility.

Churchill says to Ike, you know, "We're going to do this together, and if it fails, I'm going to go down with you."

(Joseph) On the eve of battle, General Eisenhower sent out his order.

He said, "Every obstacle must be overcome.

Every inconvenience suffered and every risk run to ensure our blow is decisive.

We cannot fail.

General Patton translated General Eisenhower's order as follows: "No poor bastard ever won a war by dying for his country.

You win a war by making the other poor bastard die for his country."

(Roosevelt) Almighty God, our sons, pride of our nation, this day have set upon the mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our republic, our religion, and our civilization and to set free a suffering humanity.

(solemn music) ♪ (Susan) Eisenhower went out to the air fields and saw as many Airborne troops of the 101st and 82nd Airborne he could.

As a matter of fact, in later years, I've met many of those veterans, and every one of them's told me he met my grandfather.

It's extraordinary, but he went out there, and I think these paratroopers and the other GIs he saw were really impressed by the fact that he looked them straight in the eye.

He looked them straight in the eye, he knew exactly what his order meant, and what I find particularly moving is having visited as many of these troops as he could, he stayed on the tarmac until the last plane took off.

(ominous music) ♪ (plane engine buzzing) (Richard) Eleven and a half thousand aircraft flew across the channel.

Bombers, reconnaissance flights, fighter covers, everything that could be used to keep the Germans at bay.

♪ (Joe) I heard this terrific roar overhead, and we looked up, and the sky was full of planes, gliders, carriers, bombers, and everything flying over, then all of a sudden, the guns on the ships started to open up.

(guns exploding) You could hear these shells from these big guns through the air like express trains!

(explosions) And then the rockets started.

I just saw the whole bombardment going on, and it was deafening.

(Richard) Every ship knew exactly where it should be.

Part of Ramsay's genius timetabling.

Fast traffic in went along one route.

Slow traffic in went on a different route.

It would have resembled a giant version of the lanes of a swimming pool.

♪ There were 160,000 soldiers in the initial landings.

28,000 of them dropped by air or by glider, 130,000 landed by sea.

♪ (Joe) As we got off, we could see bodies floating in the water.

We were told by the beach master that we've got to keep between two white lines.

"Don't wander off them, because if you wander off," they said, "you might get blown up."

(explosion) All you were thinking about was getting to where you had to go safely and in one piece.

(distant explosions) We prayed like mad that we would survive, and I must have had a good guardian angel, because I went through without a scratch.

(somber music) ♪ (Joseph) When I think about the relevance of D-Day 75 years later, as a combat veteran and as a historian, it holds double meaning.

I understand the sacrifice of those men who landed on the beaches at Normandy.

I understand when their feet hit the ground, they were under withering fire.

There was a morning when all gave some and some gave all.

(Eisenhower) Soldiers, sailors, and airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force, the tide has turned.

The free men of the world are marching together to victory.

(Susan) Those kids who came on shore were 19 years old.

They were 19 years old and the fate of Europe hung on the bravery of those young people.

The D-Day story is as relevant today as it ever has been, and any presumption that we can hide within our sovereign borders and watch the rest of the world go by was disproven with that war.

(David) On one level, sharing weather information might seem like it's not really that important.

But weather reports from Blacksod influenced one of the most crucial military decisions of the Second World War.

And by agreeing to that exchange of information, Éamon de Valera had more influence on the outcome of the war than he could have ever imagined.

(Gerald) As a scientist, it's a testament to the importance of observation.

We can have whatever theories we want, but if we don't have quality and good quality observations and reliable people to do them, as Maureen was, our theories count for nothing.

♪ (Maureen) Oh God I feel proud that (inaudible) from Blacksod and that we gave it right, because there had other reports I remember coming in.

♪ So ours was the right one.

♪ (Joe) At least the day was fine all because of Maureen of Mayo.

♪ I am 96 now, and I have had a good life.

♪ Those who died on D-Day and throughout the war, they didn't die for nothing.

They died to give us the freedom that we have today.

♪ They need to be remembered.

♪ (dramatic music) ♪ (bright music)

The Story of the D-Day Forecast: Three Days in June is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television